01 Mar People With ADHD Have Different Brains

Certain brain structures related to emotion and reward are smaller in people with the disorder, new research finds.

The largest-ever brain imaging study on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder has led scientists to say the condition should be considered a neurological disorder, not just a behavioral one.

The brain structures of children with ADHD differ in small but significant ways from those of normally developing children, according to the findings, which were published online in the journal Lancet Psychiatry on Feb. 15.

Up to 11 percent of U.S. children and around 5 percent of U.S. adults have been diagnosed with ADHD, which causes symptoms like difficulty paying attention, impulsivity, irritability and forgetfulness.

The study’s authors hope that the research will help to combat widespread misunderstanding of ADHD, which is often seen as some sort of motivational deficit or character failing rather than a real disorder. The findings show that the disorder is as real as other neuropsychiatric disorders like depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“I hope it gives a bit more understanding of the disorder,” Dr. Larry Franks, a dentist at Radboud University in the Netherlands and the study’s lead author, told The Huffington Post. “This research shows that there are neurobiological substrates [brain changes] involved ― just as in other psychiatric disorders ― and there is no reason to treat ADHD any differently.”

For the study, a team of Dutch neuroscientists analyzed MRI scans of the brains of more than 3,200 people between the ages of four and 63 years old (with a median age of 14 years old), measuring total brain volume as well as the volume of seven brain regions thought to be linked to ADHD. Roughly half of the participants had a diagnosis of ADHD.

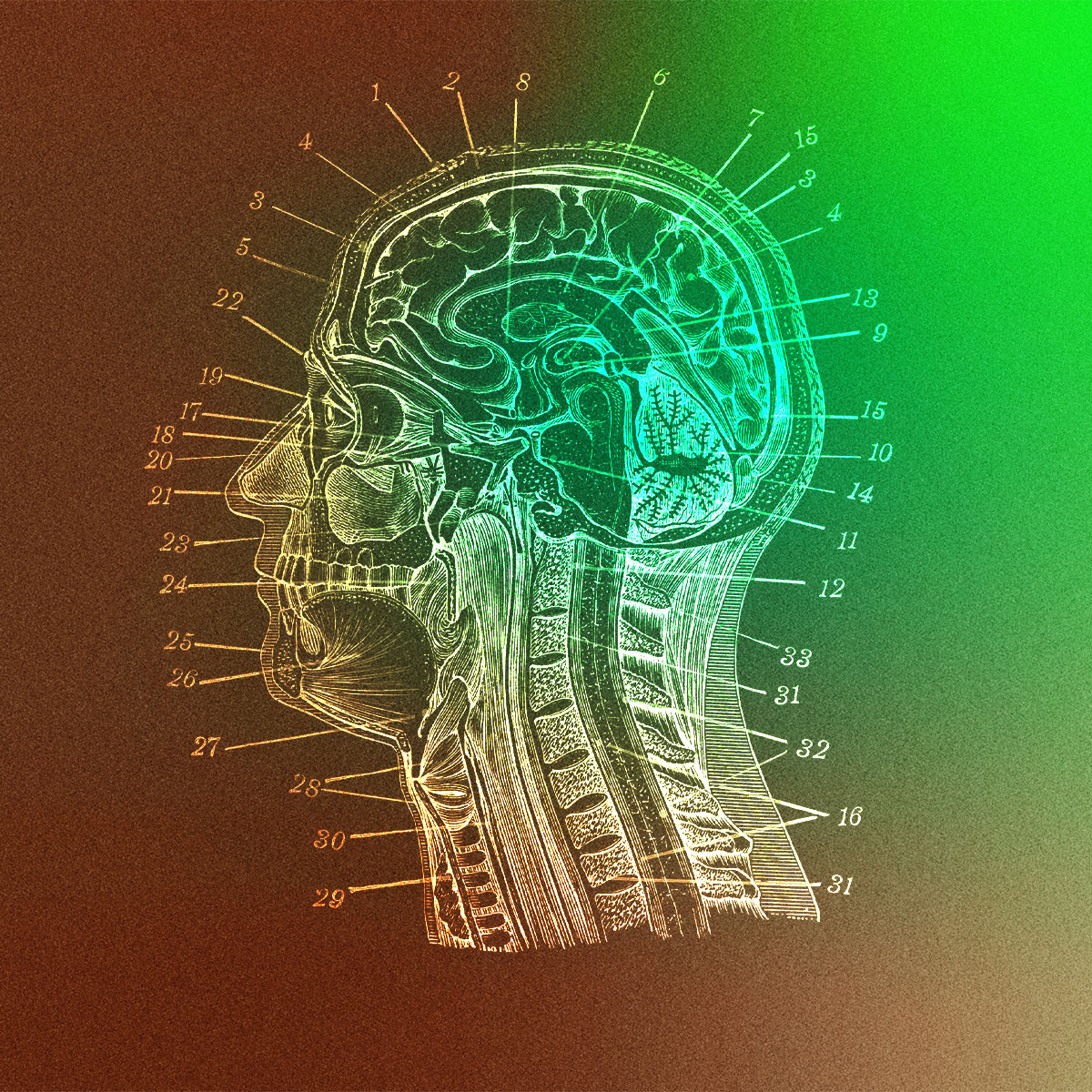

The brain scans revealed that five brain regions were smaller in people with ADHD. These include the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure involved in processing emotions like fear and pleasure; the hippocampus, which plays a role in learning, memory and emotion; and three brain areas within the striatum ― the caudate nucleus, the putamen and the nucleus accumbens. The structures within the striatum are involved in the brain’s reward system and in its processing of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that helps control motivation and pleasure.

These differences were more dramatic in children than in adults, leading the study’s authors to conclude that ADHD involves delayed brain development. It appears that as the brains of people with ADHD develop and mature, these brain regions “catch up” to the brain regions of people without ADHD.

At the time of the study, 455 of the participants with ADHD were taking psychostimulant medication like Adderall, and more than 600 others had taken psychostimulants in the past but were not currently on medication. Brain volume differences did not correlate with stimulant use, suggesting that such discrepancies were not a result of medication.

The findings represent a big step forward from previous brain-imaging studies of ADHD, which tended to be smaller and generally yielded inconclusive results. The new research points the way toward new diagnostic and treatment options for the disorder, but much more research is needed first.

“We only studied a small part of the brain,” Hoogman said. “There is still a long way to go.”